Chapter 2 R & RStudio, RMarkdown

2.1 Objectives & Resources

2.1.1 Objectives

In this lesson we will:

- get oriented to the RStudio interface

- work with R in the console

- be introduced to built-in R functions

- learn to use the help pages

- explore RMarkdown

2.1.2 Resources

This lesson is a combination of excellent lessons by others (thank you Jenny Bryan and Data Carpentry!) that I have combined and modified for our workshop today. I definitely recommend reading through the original lessons and using them as reference:

Dr. Jenny Bryan’s lectures from STAT545 at UBC

RStudio has great resources about its IDE (IDE stands for integrated development environment):

2.2 Why learn R with RStudio

You are all here today to learn how to code. Coding made me a better scientist because I was able to think more clearly about analyses, and become more efficient in doing so. Data scientists are creating tools that make coding more intuitive for new coders like us, and there is a wealth of awesome instruction and resources available to learn more and get help.

Here is an analogy to start us off. Think of yourself as a pilot, and R is your airplane. You can use R to go places! With practice you’ll gain skills and confidence; you can fly further distances and get through tricky situations. You will become an awesome pilot and can fly your plane anywhere.

And if R were an airplane, RStudio is the airport. RStudio provides support! Runways, communication, community, and other services that makes your life as a pilot much easier. So it’s not only the infrastructure (the user interface or IDE), although it is a great way to learn and interact with your variables, files, and interact directly with GitHub. It’s also a data science philosophy, R packages, community, and more. So although you can fly your plane without an airport and we could learn R without RStudio, that’s not what we’re going to do.

We are learning R together with RStudio and its many supporting features.

Something else to start us off is to mention that you are learning a new language here. It’s an ongoing process, it takes time, you’ll make mistakes, it can be frustrating, but it will be overwhelmingly awesome in the long run. We all speak at least one language; it’s a similar process, really. And no matter how fluent you are, you’ll always be learning, you’ll be trying things in new contexts, learning words that mean the same as others, etc, just like everybody else. And just like any form of communication, there will be miscommunications that can be frustrating, but hands down we are all better off because of it.

While language is a familiar concept, programming languages are in a different context from spoken languages, but you will get to know this context with time. For example: you have a concept that there is a first meal of the day, and there is a name for that: in English it’s “breakfast”. So if you’re learning Spanish, you could expect there is a word for this concept of a first meal. (And you’d be right: ‘desayuno’). We will get you to expect that programming languages also have words (called functions in R) for concepts as well. You’ll soon expect that there is a way to order values numerically. Or alphabetically. Or search for patterns in text. Or calculate the median. Or reorganize columns to rows. Or subset exactly what you want. We will get you increase your expectations and learn to ask and find what you’re looking for.

2.3 R at the console, RStudio goodies

Launch RStudio/R.

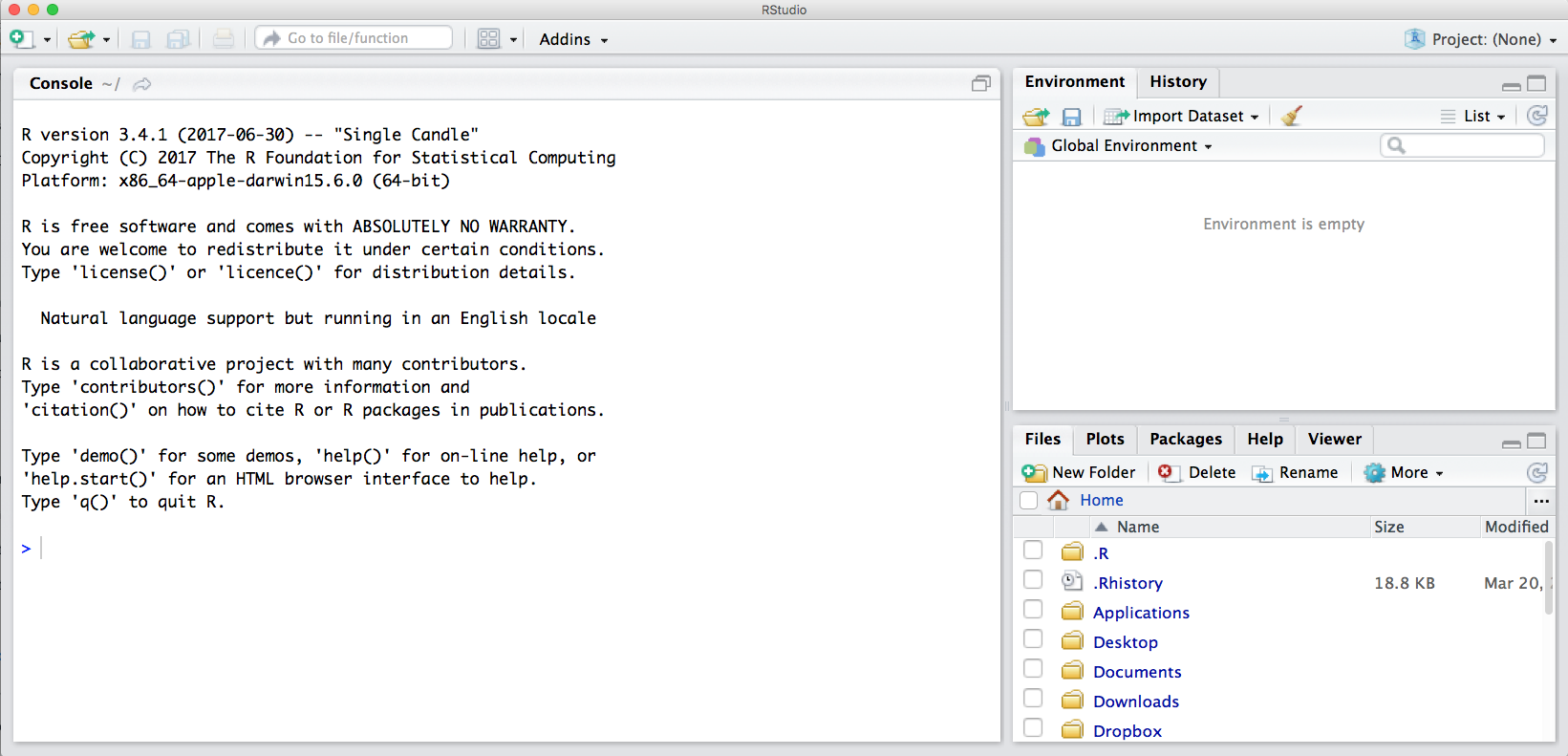

Notice the default panes:

- Console (entire left)

- Environment/History (tabbed in upper right)

- Files/Plots/Packages/Help (tabbed in lower right)

FYI: you can change the default location of the panes, among many other things: Customizing RStudio.

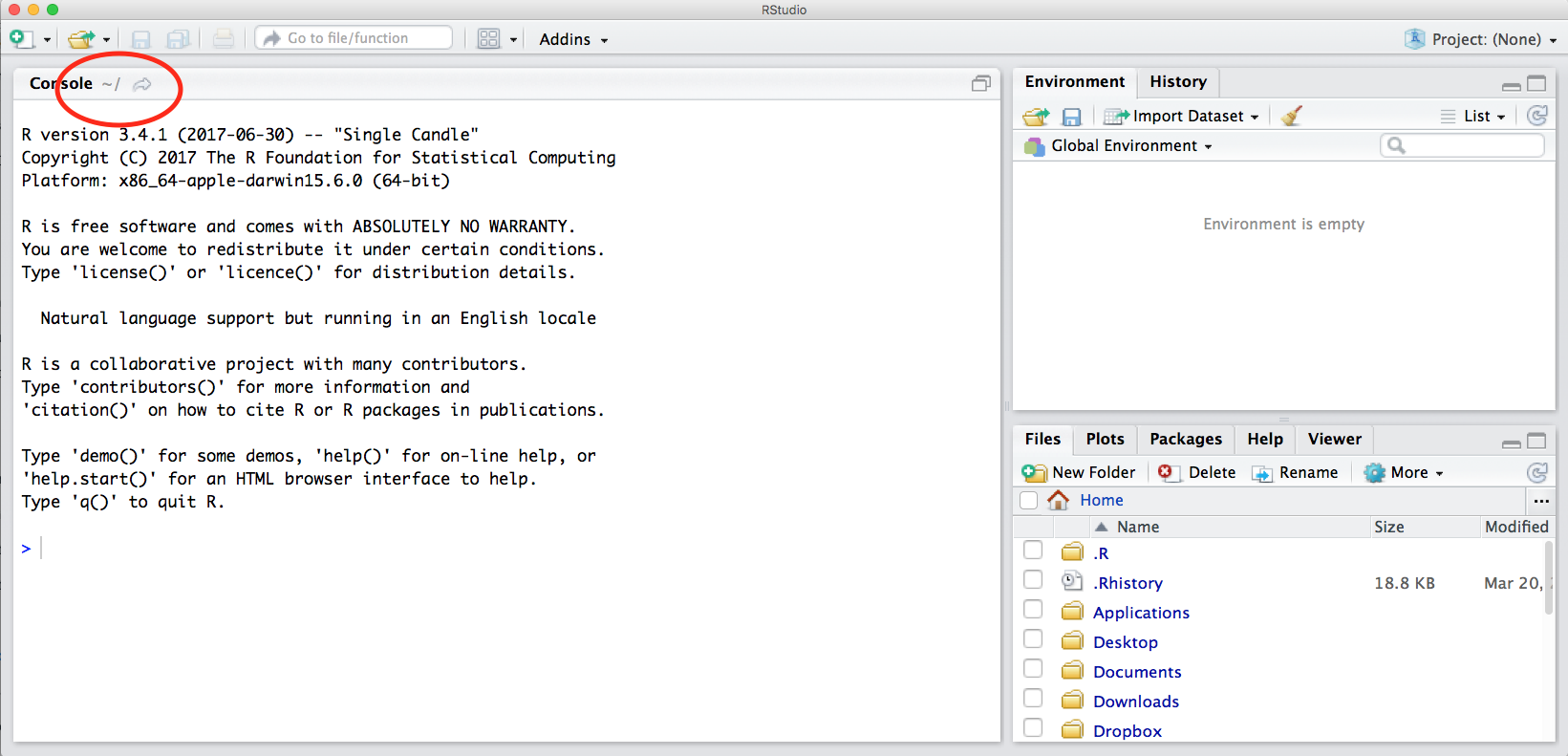

An important first question: where are we?

If you’ve have opened RStudio for the first time, you’ll be in your Home directory. This is noted by the ~/ at the top of the console. You can see too that the Files pane in the lower right shows what is in the Home directory where you are. You can navigate around within that Files pane and explore, but note that you won’t change where you are: even as you click through you’ll still be Home: ~/.

OK let’s go into the Console, where we interact with the live R process.

Make an assignment and then inspect the object you created by typing its name on its own.

## [1] 12In my head I hear, e.g., “x gets 12”.

All R statements where you create objects – “assignments” – have this form: objectName <- value.

I’ll write it in the console with a hashtag #, which is the way R comments so it won’t be evaluated.

## objectName <- value

## This is also how you write notes in your code to explain what you are doing.Object names cannot start with a digit and cannot contain certain other characters such as a comma or a space. You will be wise to adopt a convention for demarcating words in names.

Make an assignment

To inspect this variable, instead of typing it, we can press the up arrow key and call your command history, with the most recent commands first. Let’s do that, and then delete the assignment:

## [1] 2.5Another way to inspect this variable is to begin typing this_…and RStudio will automagically have suggested completions for you that you can select by hitting the tab key, then press return.

One more:

You can see that we can assign an object to be a word, not a number. In R, this is called a “string”, and R knows it’s a word and not a number because it has quotes " ". You can work with strings in your data in R pretty easily, thanks to the stringr and tidytext packages. We won’t talk about strings very much specifically, but know that R can handle text, and it can work with text and numbers together (this is a huge benefit of using R).

Let’s try to inspect:

2.3.1 Error messages are your friends

Implicit contract with the computer / scripting language: Computer will do tedious computation for you. In return, you will be completely precise in your instructions. Typos matter. Case matters. Pay attention to how you type.

Remember that this is a language, not unsimilar to English! There are times you aren’t understood – it’s going to happen. There are different ways this can happen. Sometimes you’ll get an error. This is like someone saying ‘What?’ or ‘Pardon’? Error messages can also be more useful, like when they say ‘I didn’t understand what you said, I was expecting you to say blah’. That is a great type of error message. Error messages are your friend. Google them (copy-and-paste!) to figure out what they mean.

And also know that there are errors that can creep in more subtly, when you are giving information that is understood, but not in the way you meant. Like if I am telling a story about suspenders that my British friend hears but silently interprets in a very different way (true story). This can leave me thinking I’ve gotten something across that the listener (or R) might silently interpreted very differently. And as I continue telling my story you get more and more confused… Clear communication is critical when you code: write clean, well documented code and check your work as you go to minimize these circumstances!

2.3.2 Logical operators and expressions

A moment about logical operators and expressions. We can ask questions about the objects we made.

==means ‘is equal to’!=means ‘is not equal to’<means ` is less than’>means ` is greater than’<=means ` is less than or equal to’>=means ` is greater than or equal to’

## [1] FALSE## [1] TRUE## [1] TRUEShortcuts You will make lots of assignments and the operator

<-is a pain to type. Don’t be lazy and use=, although it would work, because it will just sow confusion later. Instead, utilize RStudio’s keyboard shortcut: Alt + - (the minus sign). Notice that RStudio automagically surrounds<-with spaces, which demonstrates a useful code formatting practice. Code is miserable to read on a good day. Give your eyes a break and use spaces. RStudio offers many handy keyboard shortcuts. Also, Alt+Shift+K brings up a keyboard shortcut reference card.

My most common shortcuts include command-Z (undo), and combinations of arrow keys in combination with shift/option/command (moving quickly up, down, sideways, with or without highlighting.

When assigning a value to an object, R does not print anything. You can force R to print the value by using parentheses or by typing the object name:

weight_kg <- 55 # doesn't print anything

(weight_kg <- 55) # but putting parenthesis around the call prints the value of `weight_kg`## [1] 55## [1] 55Now that R has weight_kg in memory, we can do arithmetic with it. For

instance, we may want to convert this weight into pounds (weight in pounds is 2.2 times the weight in kg):

## [1] 121We can also change a variable’s value by assigning it a new one:

## [1] 126.5And when we multiply it by 2.2, the outcome is based on the value currently assigned to the variable.

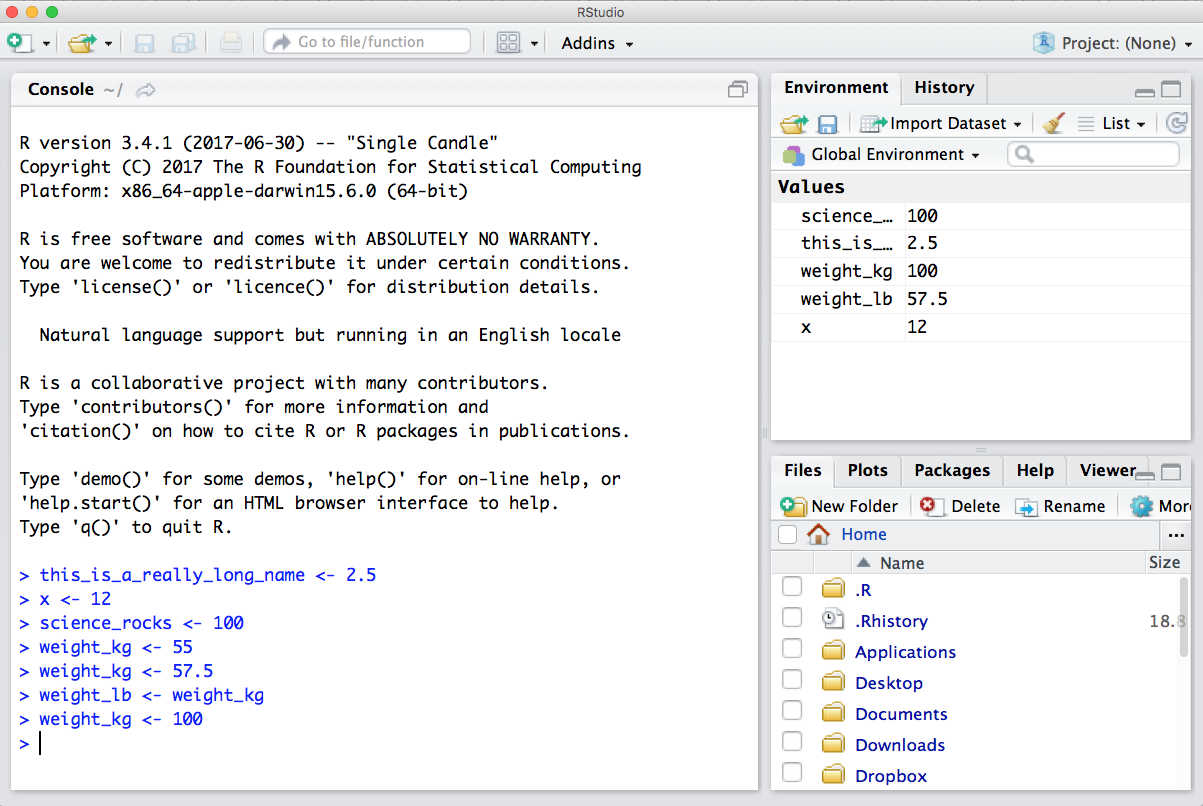

OK, let’s store the animal’s weight in pounds in a new variable, weight_lb:

and then change weight_kg to 100.

What do you think is the current content of the object weight_lb? 126.5 or 220? Why?

It’s 125.6. Why? Because assigning a value to one variable does not change the values of

other variables — if you want weight_kg updated to reflect the new value for weight_lb, you will have to re-execute that code. This is why we re-comment working in scripts and documents rather than the Console, and will introduce those concepts shortly and work there for the rest of the day.

We can create a vector of multiple values using c().

## [1] 126.5 100.0## [1] "Jamie" "Melanie" "Julie"2.4 Your Turn

Exercise 1. Create a vector that contains the different weights of four fish (you pick the object name!):

- one fish: 12 kg

- two fish: 34 kg

- red fish: 20 kg

- blue fish: 6.6 kg

2. Convert the vector of kilos to pounds (hint: 1 kg = 2.2 pounds)

3. Calculate the total weight

fish_weights <- c(12, 34, 20, 6.6)

fish_weights_lb <- fish_weights * 2.2

sum(fish_weights_lb) #we haven't gone over functions like `sum()` yet but this is covered in the next section## [1] 159.722.5 R functions, help pages

R has a mind-blowing collection of built-in functions that are used with the same syntax: function name with parentheses around what the function needs to do what it is supposed to do. function_name(argument1 = value1, argument2 = value2, ...). When you see this syntax, we say we are “calling the function”.

Let’s try using seq() which makes regular sequences of numbers and, while we’re at it, demo more helpful features of RStudio.

Type se and hit TAB. A pop up shows you possible completions. Specify seq() by typing more to disambiguate or using the up/down arrows to select. Notice the floating tool-tip-type help that pops up, reminding you of a function’s arguments. If you want even more help, press F1 as directed to get the full documentation in the help tab of the lower right pane.

Type the arguments 1, 10 and hit return.

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10We could probably infer that the seq() function makes a sequence, but let’s learn for sure. Type (and you can autocomplete) and let’s explore the help page:

The help page tells the name of the package in the top left, and broken down into sections:

- Description: An extended description of what the function does.

- Usage: The arguments of the function and their default values.

- Arguments: An explanation of the data each argument is expecting.

- Details: Any important details to be aware of.

- Value: The data the function returns.

- See Also: Any related functions you might find useful.

- Examples: Some examples for how to use the function.

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10## [1] 1 3 5 7 9The above also demonstrates something about how R resolves function arguments. You can always specify in name = value form. But if you do not, R attempts to resolve by position. So above, it is assumed that we want a sequence from = 1 that goes to = 10. Since we didn’t specify step size, the default value of by in the function definition is used, which ends up being 1 in this case. For functions I call often, I might use this resolve by position for the first

argument or maybe the first two. After that, I always use name = value.

The examples from the help pages can be copy-pasted into the console for you to understand what’s going on. Remember we were talking about expecting there to be a function for something you want to do? Let’s try it.

2.5.1 Your turn

Exercise: Talk to your neighbor(s) and look up the help file for a function that you know or expect to exist. Here are some ideas:

?getwd(),?plot(),min(),max(),?mean(),?log()).

And there’s also help for when you only sort of remember the function name: double-question mark:

Not all functions have (or require) arguments:

## [1] "Tue Jul 18 09:44:00 2023"2.6 Packages

So far we’ve been using a couple functions from base R, such as seq() and date(). But, one of the amazing things about R is that a vast user community is always creating new functions and packages that expand R’s capabilities. In R, the fundamental unit of shareable code is the package. A package bundles together code, data, documentation, and tests, and is easy to share with others. They increase the power of R by improving existing base R functionalities, or by adding new ones.

The traditional place to download packages is from CRAN, the Comprehensive R Archive Network, which is where you downloaded R. You can also install packages from GitHub, which we’ll do tomorrow.

You don’t need to go to CRAN’s website to install packages, this can be accomplished within R using the command install.packages("package-name-in-quotes"). Let’s install a small, fun package praise. You need to use quotes around the package name.:

install.packages("praise")Now we’ve installed the package, but we need to tell R that we are going to use the functions within the praise package. We do this by using the function library().

What’s the difference between a package and a library?

Sometimes there is a confusion between a package and a library, and you can find people calling “libraries” to packages.

Please don’t get confused: library() is the command used to load a package, and it refers to the place where the package is contained, usually a folder on your computer, while a package is the collection of functions bundled conveniently.

Now that we’ve loaded the praise package, we can use the single function in the package, praise(), which returns a randomized praise to make you feel better.

## [1] "You are glorious!"2.7 Clearing the environment

Now look at the objects in your environment (workspace) – in the upper right pane. The workspace is where user-defined objects accumulate.

You can also get a listing of these objects with a few different R commands:

## [1] "fish_weights" "fish_weights_lb" "names" "science_rocks"

## [5] "this_is_a_really_long_name" "weight_kg" "weight_lb" "x"## [1] "fish_weights" "fish_weights_lb" "names" "science_rocks"

## [5] "this_is_a_really_long_name" "weight_kg" "weight_lb" "x"If you want to remove the object named weight_kg, you can do this:

To remove everything:

or click the broom in RStudio’s Environment pane.

For reproducibility, it is critical that you delete your objects and restart your R session frequently. You don’t want your whole analysis to only work in whatever way you’ve been working right now — you need it to work next week, after you upgrade your operating system, etc. Restarting your R session will help you identify and account for anything you need for your analysis.

We will keep coming back to this theme but let’s restart our R session together: Go to the top menus: Session > Restart R.

2.8 RMarkdown

Now we are going to also introduce RMarkdown. This is really key for collaborative research, so we’re going to get started with it early and then use it for the rest of the day.

This is also going to introduce us to the fact that RStudio is a sophisticated text editor (among all the other awesome things). You can use it to keep your files and scripts organized within one place (the RStudio IDE) while getting support that you expect from text editors (check-spelling and color, to name a few).

An RMarkdown file will allow us to weave markdown text with chunks of R code to be evaluated and output content like tables and plots.

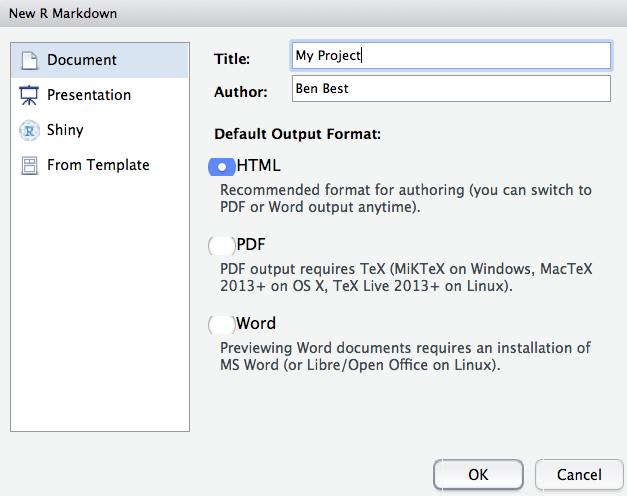

File -> New File -> RMarkdown… -> Document of output format HTML, OK.

You can give it a Title like “My Project”. Then click OK.

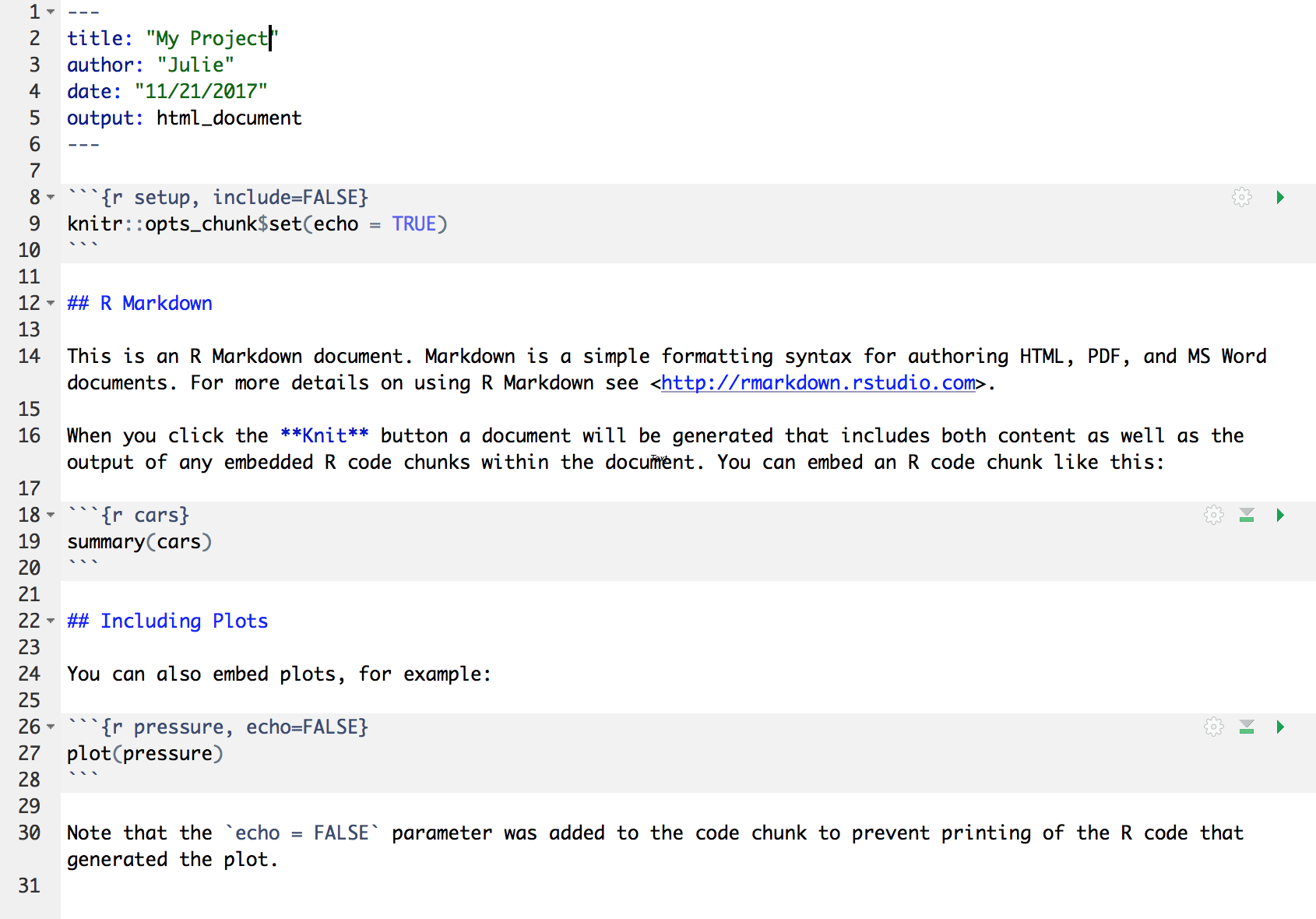

OK, first off: by opening a file, we are seeing the 4th pane of the RStudio console, which is essentially a text editor. This lets us organize our files within RStudio instead of having a bunch of different windows open.

Let’s have a look at this file — it’s not blank; there is some initial text is already provided for you. Notice a few things about it:

- There are white and grey sections. R code is in grey sections, and other text is in white.

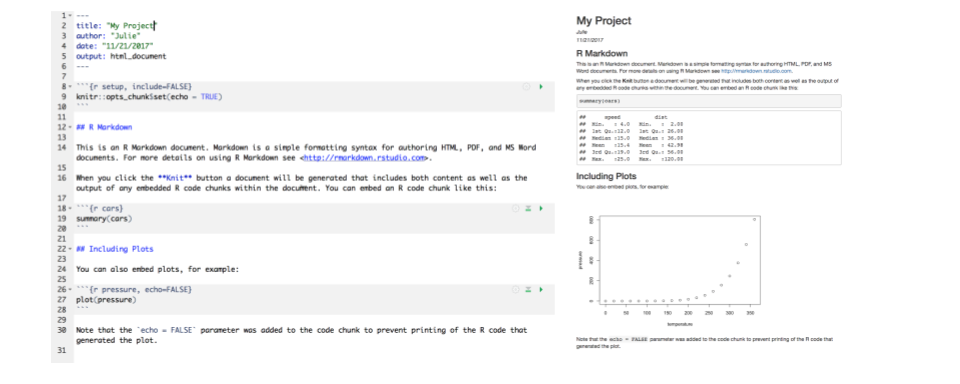

Let’s go ahead and “Knit HTML” by clicking the blue yarn at the top of the RMarkdown file.

What do you notice between the two? So much of learning to code is looking for patterns.

Notice how the grey R code chunks are surrounded by 3 backticks and {r LABEL}. These are evaluated and return the output text in the case of summary(cars) and the output plot in the case of plot(pressure).

Notice how the code plot(pressure) is not shown in the HTML output because of the R code chunk option echo=FALSE.

The hashtag (#) at lines 12 and 22 cause the following text to be displayed larger and in bold.

This RMarkdown file has 2 different languages within it: R and Markdown.

We don’t know that much R yet, but you can see that we are taking a summary of some data called ‘cars’, and then plotting. We will focus on R for the rest of the workshop, but for the rest of this morning let’s focus on the second language.

The second language is Markdown. This is a formatting language for plain text, and there are only about 15 rules to know.

Notice the syntax for:

- headers get rendered at multiple levels:

#,## - bold:

**word**

There are some good cheatsheets to get you started, and here is one built into RStudio: Go to Help > Markdown Quick Reference

Important: note that the hashtag # is used differently in Markdown and in R:

- in R, a hashtag indicates a comment that will not be evaluated. You can use as many as you want:

#is equivalent to######. It’s a matter of style. I use two##to indicate a comment so that it’s clearer what is a comment versus what I don’t want to run at the moment. - in Markdown, a hashtag indicates a level of a header. And the number you use matters:

#is a “level one header”, meaning the biggest font and the top of the hierarchy.###is a level three header, and will show up nested below the#and##headers.

If this seems confusing, take comfort in the fact that you are already used to using #s differently in real life: it can mean “number” or “pound” or hashtags on social media.

Learn more: http://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/

2.8.1 Your Turn

- In Markdown write some italic text, make a numbered list, and add a few subheaders. Use the Markdown Quick Reference (in the menu bar: Help > Markdown Quick Reference).

- Reknit your html file.

2.8.2 Code chunks

OK. Now let’s practice with some of those commands that we were working on this morning.

Create a new chunk in your RMarkdown first in one of these ways:

- click “Insert > R” at the top of the editor pane

- type by hand ```{r} ```

- if you haven’t deleted a chunk that came with the new file, edit that one

Now, let’s write some R code.

x <- seq(1:15)Now, hitting return does not execute this command; remember, it’s a text file in the text editor, it’s not associated with the R engine. To execute it, we need to get what we typed in the the R chunk (the grey R code) down into the console. How do we do it? There are several ways (let’s do each of them):

- copy-paste this line into the console.

- select the line (or simply put the cursor there), and click ‘Run’. This is available from

- the bar above the file (green arrow)

- the menu bar: Code > Run Selected Line(s)

- keyboard shortcut: command-return

- click the green arrow at the right of the code chunk

2.9 RMarkdown video (1-minute)

Let’s watch this to demonstrate all the amazing things you can now do:

2.10 Troubleshooting

Here are some additional things we didn’t have time to discuss:

2.10.1 I entered a command and nothing’s happening

It may be because you didn’t complete a command: is there a little + in your console? R is saying that it is waiting for you to finish. In the example below, I need to close that parenthesis.

2.10.2 How do I update RStudio?

To see if you have the most current version of RStudio, go to the Help bar > Check for Updates. If there is an update available, you’ll have the option to Quit and Download, which will take you to http://www.rstudio.com/download. When you download and install, choose to replace the previous version.